|

|

|||

|

Bruno Helsdown

|

|||

|

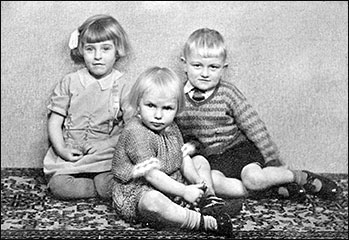

Childhood

|

|||

|

My dad remembered being told, "Go and fetch the lasts." He didn’t live too far from the factory—it was on the same road—but he said "They were so heavy! I dragged them along and by the time I got home, of course, there'd be one missing!" He would have to shoot back to the street to try and find it. Then, they would put them all in a big box together. (They would make part of the shoe on the last and then take it back to the factory.)

If the shoes had the slightest mark, they were thrown out as rejects. All the factory workers would go to the factory and ask, "Are there any rejects?" My dad managed to get a pair - they called them rejects at the time - and he brought them home. I still have that pair of shoes today. They must be 60 years old now. I had them resoled and they are fantastic. Grenson shoes are high quality! They sold to the top shops. My Mother's Family in Rushden My maternal grandfather, Charlie Dorks, was a bit of a wanderer, would leave the house on Monday, and wherever he could get a job for a decent price, he did it. If a bloke said, "Do you want to move up to [so-and-so]?" then he would. At one point, he finished up in Warton, up in Cumbria. He wrote a letter to my mother and his wife saying: "If you want to come, I'm up here. I've got six months' work! You can stop with me for six months." So they did. My mother and grandmother stopped with him up there, leaving the rest of the family down in Rushden—the oldest girls were left to look after the house on Spencer Road. The six months became one year before they came back. When my grandfather ('Gramps') finished work in the 1960s, he set up his own business. I can remember times, biking around Rushden as a child, when I would see my gramps sitting on his stool with five gallons of creosote, creosoting people's fences. The gas house in Rushden allowed us to make our own gas. The coal made gas and finished up as coke, and the by-product was this sticky tar stuff - gas tar and creosote. It you creosote your fence, you never need to creosote it again! But if you got it on your skin, it burnt you. My gramps sat on his stool with his cap on and his paint, creosoting fences, and he made a good living out of it. That was my mum's dad. Mum and Dad When my mother, Constance, and my father, Bruno, married, they had two rooms. That was how they did it in those days. A lot of people who lived on their own would say, "Does anyone want two rooms?" - a spare spot in their house for a newly married couple to live. My grandmother, who lived in a house built for her on Spencer Road in Rushden with her 12 children (no one could figure out where she got the money from!), managed to find two rooms for my parents opposite her with a family called Scroxton. That is where I was born. My parents' relationship was a bit of a disaster, really. The first time they parted, my father was at the Windmill Club. We were little children, and my mum said to us, "Go and fetch your dad. Tell him I am getting the dinner ready." So off we went to the Windmill Club, and at 1pm we all came back to find no one there - and no dinner! We all looked at one another, wondering what had happened. "Your mum's left us," Dad said, and he cried his eyes out. We all cried our eyes out. Soon, the decision was made to go down to Grandma Dorks's house, where she made us food and looked after us. We found out where Mum was living after that. She had gone to live with her oldest sister, who had no children. Grandma said, "Come on, Tony. We're going to Northampton. We're going to knock on this door, where your mum is, and we are going to tell her we want her home." So that is what we did. Mum first agreed that she would come back the next week, but we had a taxi outside waiting for her, so we convinced her to pack up her belongings and we brought her back home. Mum and the Sixpence In 1936 there was plenty of fruit about, but we could never afford it. My father was paid £2.10 a week. He was paid this amount for 20 years. There was no inflation, and it never changed. He got £2.10 for ages. With this, he had to pay the mortgage, put money aside for the gas and electric and put the rest aside for groceries. One Monday morning, my mum handed me a sixpence and told me to run to the Co-op and get a bag of sugar. "For God's sake, don't lose that sixpence!" she said. That's the only bit of money I have got until the end of the week." So off I went, short trousers on, of course. There was a building plot nearby - a bit of grass - that we used to cut through to get to Co-op. When I got to the other side ... I had not got the sixpence. By now, my grandma had sold her place at Spencer Road and had bought a new place nearby. I'll go and tell Grandma, I thought. I nipped around to hers. "Go and fetch your mum," she told me. All three of us went to the building plot and were combing through the grass on our hands and knees, like they do today when they are hunting for clues, and, luckily, we found it! "I'm never going to give you any more money," Mum told me after that. Dad and HE Bates When my father was at Newton Road School, he was in the same class as HE Bates, who later wrote the book Love for Lydia. I it is based around Rushden, the town, because we have got a lovely big manor house in Hall Park, where the council meets today. When I was a child, HE Bates came back to Rushden to do an event, and he specially requested to his relations, "Make sure Bruno's there.” My dad went, and I went out with him. At the event, the room was full. HE came up to me and said, “Want to hear a story about your dad, Bruno?” Of course I did, I replied. “Well, the headmaster called him to get the cane, because he had done something wrong. So, your father went out there and held his hand out. The headmaster caned him, and with the other hand, your dad woofed the headmaster, a solid punch to the jaw, and put him on the floor! He tried to get up and your dad pinned him down. The class erupted! Some of the older boys managed to pull him off, but I don’t know what happened after that, whether he got expelled. It was never mentioned." I asked, "Is that right, Dad? Did you attack the headmaster? Did he bar you from school?" "No," Dad said. "In actual fact, we finished up shaking hands." HE Bates told us this story was in his book - the blonde boy who attacked the headmaster after getting caned! "That's all I remember you for," HE Bates told my dad. Childhood Memories My parents could not move into a council house until they had children. In 1931, we moved to a council house on Tennyson Road in Rushden. We were lucky, when we moved, that my father knew the head mechanic at the factory - a bloke named Sinfield. They had taken all the old machinery out of the factory and had electrified all the machines. "Bruno," Sinfield said, "I know you've got five kids and could do with the money. The work's got to be done on the weekends. Do you want to come with me?" My dad said, "I wouldn't mind working weekends, but I don't want to come in early on Sunday mornings." We always had a good Sunday dinner, a roast, and baked potatoes and Yorkshire puddings, and he did not want to miss it. This work helped pay for the mortgage and get some furniture in the house. I remember going down with my dad in the engine room and seeing a big engine with a big wheel that provided all the power for the factory. It went Shoom, shoom. It was a dangerous place in which to work. If one of the sharp valves snapped, it would clout a bloke on the head! In the house on Tennyson Road, we had a fireplace with a little grate and two openings in the side. We never had a gas stove, so my mother did the dinner in the grate. When we got up in the morning, it was as cold as anything. There was no insulation in the walls, and we had more frosts and very bad winters then. There would often be more frost on the inside of the bedroom windows than there was outside! Sometimes, my dad would bring bits home from the shoe factory and - if they were throwing the old wooden lasts away - he would put them on the fire. These wooden lasts were made from special wood that was highly polished. They lasted for a long while on the fire. We would get up, have a little bowl of porridge and go off to school. I wore short trousers, no underpants or vest, a shirt, a pullover and a coat. But I remember being cold! My mother never liked living in the house on Tennyson Road. After my grandmother helped my parents get back together again, she said "Right!" and put a £50 deposit down on a house that was just about to be completed. The total cost of the house was £450 - you would not get a house for that nowadays! We moved to Blinco Road on 7th August 1936, three years before the war. The old lorry came around, we put in what little furniture we had, the kids jumped in the back and off we went. Blinco Road is quite an unusual name for a road, but we could never figure out where it came from. The house on Blinco Road was semi-detached, right on the edge of Rushden. Our house was right at the end and, although they had finished building the houses, the road was not finished; it was still muddy. Step out of our door, though, and you would find yourself looking over fields, allotments and the cricket ground. It was the perfect place. When we lived on Blinco Road, there was a fish and chips van that used to come round every Friday night. We would always have fish and chips then, and I got to know the lady in the van quite well. Her husband did the driving. I knew what time the van would come, and I would race right down to the bottom of the road, right before the van came to its first stop, off Tennyson Road. I would stand in line and order two punnets of chips and four pieces of fish. I think 1 remember right that was eight pence. Eight pence! If you wanted that today, you would be paying £20or £30 due to inflation. It was cod and chips, and they really were big chunks of fish. The kids and my mum had half each, and my dad had a full one. The lady in the van used to give me some chips and batter bits. When they fry fish, they shake it a bit before they chuck it in the basket at the top, and there are all these batter bits falling back into the oil. They threw all these batter bits into a big pan and she always gave me some. They were really crispy. Schooldays I started school at four years old, when we still lived at Tennyson Road I went to Alfred Street School and moved up to Newton Road School in 1936 when I was six years old. One thing I remember about Alfred Street School is that I used to run away a lot. At this particular time, the headmistress, Mrs Swan, said to my sister Betty, "Why isn't your brother at school." "Well, he is," Betty replied, "because I brought him." "He hasn't been in class for three days." "But I brought him down to school!" "Right," said the headmistress. "I had better go see your mother." So, she went up to see my mother. My mother knew where I was. 'They're digging a road out at Rose Avenue. There's a digger there and he's fascinated by it." She was right. I went up to this digger and the bloke asked, "Why aren't you at school?" "I've got diphtheria," I told him. "Oh," he said. "Are you cleared then, now?" "Yep," I said. I’ve got to go to school next week." "Come here," he said, and he put me on his lap. I thought it was marvellous! He swung the digger around, then I saw my mother and the school headmistress coming up. I jumped out and rushed over to my mother. This would have been at about 10am. "OK, Mrs Helsdown," Mrs Swan said. "I'll look after him." She pulled on my wrist and took me down to the school, put me in her office and then locked the door. "You’ve been a very, very naughty boy," she said. "You're not coming out." At 4pm Betty came in and Mrs Swan said, "Bet, bring him in the morning. I want him in this office." I did not try to run away again. About 30 or 40 years later, I was building a warehouse opposite to where this old lady lived. She came over and said, "Do you mind - my ceiling's falling down. Can you help me?" I agreed to have a look, and it was a dirty old job. She needed a whole new ceiling. "Can you do it?" she asked, and we did it for her. When she came to ask for the bill, I asked her what her name was. "Mrs Swan," she replied. I just sat there, and she looked at me. I cannot remember how I looked. "You haven't got any relations who were headmistress at Alfred Street School?" I asked "No," she said, over the moon. "I was the headmistress! You were the naughtiest boy I could ever imagine. I hope you've changed." "Not much!" I said, and we both had a good laugh. She looked like a very old lady. "Have you done well in life?" she asked. "I've done very well," I replied. From then on, she told us she would sit in her bedroom and look at us working. If it was raining, she would come out to us and say, "I've got the teapot on! Instead of sitting in your lorry, come in and have a cup of tea." Coronation of King George VI I remember the coronation of King George VI in 1937. I was six or seven years old. Alfred Street School, where I went to school, had decided that they would put a bus on, going all around Rushden, because everybody had the day off for the celebration. The streets and every house in Rushden were all decorated, and it was very exciting being on this bus! At the end, when we came back to school, they had laid all those cakes and lemonades out. It was a long day in Rushden and afterwards 1 went to my Grandma's on Cromwell Road. There was a parade too - it was a joyful time! Mr Dodge and the 11 Plus In my final year of junior school, I did 11 plus. I did not like it. I remember the teacher, Mr Dodge, who sat there in front of us. He had given us some work to do and, after 10 minutes, I stood up and handed him the paper. He looked at the paper and back up at me. "Have you finished, Helsdown?" "Yes," I replied. "Well," he said, "you're either brilliant or you've put a load of rubbish on this bit of paper. You can go home now." I did not need to be told twice. I went home! Needless to say, I did not pass the exam and went to an intermediate school until I was 14. Just out of the navy, when I was around 25 years old, I saw Mr Dodge again. He was surprised to see me and asked how well I had done in life. I told him exactly what I was up to. "You know," he said when I had finished, "I always knew your hands were going to make you a fortune - because it wasn't going to be this - and he pointed at his head. Playing Around We were always in the fields when we were kids. We had no watches so there was no sense of time. Often when we were playing, we never even thought about dinner because we used to pick stuff out of the field. We would pick blackberries and mushrooms and fresh watercress right out of the river. We would make our own hand warmers when it was cold. This was a cocoa tin with a bit of touchwood in. We would put a bit of wire round the tin as a handle, light the touchwood and run up and down the street, smoke coming out of the back. We would play hockey on the road, and if we saw a car coming, we knew it was the doctor's car because all the undertakers came up with horses. We very rarely saw a car, so we mainly played outside on the road. When I was a bit older I wanted a bike. We went to the tip and collected two bike wheels we used to make our own bikes! They were not safe on the road, but we used to make our own enjoyment. That is one of the things I remember. When I was young, nobody went to the seaside. We all walked down to Ditchford, where there was a river in which we would all swim underneath a bridge. We used to go down there in the summer on every Sunday afternoon that was nice, with a bottle of cold tea and some jam sandwiches. The whole family would go (there were only three of us children then) and we enjoyed it. There were about 50 other families there too. It was like our Blackpool! Locally, it was known as 'Ditchford-by-Sea'. In Ditchford I was always in the water. There were rocks down there because there is a canal on the side of the river, and sometimes I would go with the bigger boys. We would stand on the side of the lock and look at the water; it was a long way down! This one time, they said, "Bruno, if you want to come with us, you've got to learn to swim." They all dived down into the lock - such a long way! "OK, Bruno, jump down." "No," I said, "I'm not going to jump down there!" "If you don't jump down, you can't come down with us." So, I jumped! They were waiting for me, and as I came up again, they put me on the ladder. And that is what got me swimming. It was pretty good of them, the elders, and of course Rushden had a swimming pool, so I could practise there. On one particular day, it was very bright, hot and sunny, and I passed out on the grass. As luck would have it, the local doctor happened to be going over the bridge in his car, and there were some fishermen on the bridge fishing, and they shouted, "Stop the doctor!" They knew it was him because he was the only one with a car: a green Austin 7. (Doctor Greenfield in the green car!) He was a lovely man, and he got out of his car. He had a look at me and apparently he picked me up in his arms I cannot remember this myself - and carried me to his car, putting m in the back, with my mother sitting in the front. "This is sunstroke," he said. "Let s get him home, put a cold bandage on his head and cool him down a bit. He'll be all right in the morning. No need to bring him to the surgery." The Jackdaw I was about eight years old when a bloke in Rushden said to me, "Bruno, come here! I’ve got something for you." He pulled out an apple box out of a bag. The box had a bit of wire on the top and a water drip attached. Inside the box was a bird. "See this jackdaw?" he said. "I've got to go into the army, and I've got to go to India. I want you to look after this until I come home." He put it back into the bag and gave it to me. If you joined the Indian Army, it meant you were there for seven years. I did not know what to do! I took it home. My dad came back from work and asked me, "What have you got there?" "It's a jackdaw." "You can't keep it like that in a box," he said. "I can make it a cage tomorrow," I said. "I'll just have to go and set some wood." The next day, I made him a proper cage but still my dad was not happy. "You can't take a wild bird home. Let it go." So, I opened the top of the cage and it flew off. Later, I was sitting on the top bit of the side gate and looked around for it. I started making jackdaw noises - "Jak! Jak!" - and it came back! The jackdaw sat next to me on the gate. I knew how to catch him from then on; you could attract him with something shiny on your finger. That, then, was the talk of Rushden. The county cricket team would come and play once a year at the cricket ground just beyond our house. Middlesex came one year, and they were thrashing Northamptonshire. Dad and I were sitting on the bed in the back bedroom, which overlooked the cricket field. "They're losing again," he said, "Send the jackdaw around." The jackdaw shot around the cricket pitch two or three times then came back home. Of course, the bowler would see this bird flying around and it broke his concentration. From then, the game all went to pieces. They were standing, looking over up to where we were and shouted, "Call that jackdaw back!" which we did and put it back in its cage. It was a funny time! I never gave the jackdaw a name; I just called it 'Jack'. Two years after, it stopped coming home. Dad and I were very concerned, so we went out looking for him. Later on, a bloke said to me, "Did you ever find out what happened to your jackdaw, Bruno?" "No," I said. "A man, Tod Jolley, shot him. He was a one-armed bloke who lived down the end of the street." He had lost his arm in the First World War. "It appears he got his gun and started picking off all the birds near him." It was a shame! I never saw the man who gave me the bird again. Memories of Grandma Dorks I used to go up to Grandma Dorks's house a lot when I was a kid. She used to say, "Come on, Tony, I'll give you a piece of bread." Dead opposite her there was a house that had been turned into a bakery. This bakery did all the local loaves, straight out of the oven. The baker left Grandma's loaf on one side, so she could just go in there, pick the loaf up and leave the money. Grandma made blackberry jam, and she would cut off the knobby (that's the end bit), add butter and blackberry jam. I have never tasted anything so nice. She would take me down to Spencer Park. She even made me a kite (mind you, it did not fly because it was too heavy); she was a lovely old lady. That was my mum's mum. Jobs When I was 12 years old, 1 got a paper round in the morning. I was at Newton Road School at this point. My mum said to me, "I’ve got you a butcher's round." "When?" I asked her. "In the morning!" "But I've got a paper round in the morning!" "We can get some extra meat if you work for the butcher's shop." You see, meat was rationed then, so I agreed to do it. In the mornings, I did my paper round, my butcher's round and just got to school at 9.30am. When I was a bit older, I got a job at Co-op doing the groceries. I was a good, strong boy so I would get the spuds out of the sack and put them in the boxes. I would work the bacon slicer and do other odd-end jobs. I had the paper round, butcher's round, and now I was out at night! In 1942, because of the war, all the blokes were called up to join the services. The girls from the Women's Land Army were left to work the farms - and there were some jobs that they could not or would not do. So, Mr Harris, who worked up at Newton Farm in Newton Bromswold, came to our school in August looking for some help. "I need two good, strong lads," he told the headmaster, Mr Billy Sherwood, "to help with the beets and the harvesting for two months." When Billy Sherwood asked my class, he was not surprised when my hand shot up first. The other person to put his hand up was my friend Pete Dobbs. That was another paid job for me (and a chance to get away from school!). We were told to be at Newton Farm the next Monday morning at 7.30am. Working on the farm was us two boys and two Land Army Girls, and we worked hard. Our first job was seeding the beets - which we called 'Mangle-Wurzels' - and making sure they had enough space to grow. We had to thin them out because they fed them to the cattle. Sometimes, I would even take one home myself to eat with my mashed potato. It reminded me a lot of turnips, which I still love to have with my potatoes today. Next up was harvesting the barley. There was an old-fashioned cutter which wrapped the barley up in sheaves. When it shot them out, would take two under each arm and pile them in eights. These were left for two weeks to dry out. After 12 days the sheaves were dry, so we went round again, but this time I was on a big two-wheeled horse and cart with a long rope from the horses bridle. The land girls would hook up these sheaves with a pitchfork onto the trailer. The pile would build up and up and up, and when there was enough, I would be about 12 feet off the ground on top of the straw! "Come on," I would say to the horse, and we would go back to the end of the field. There would be two more people unloading and making haystacks here. It was hard work, but the farmer’s wife and sister used to come up every night with a big enamel jug full of tea, with homemade bread and raspberry or strawberry jam. It was heaven. Working on the farm was a happy time for me. I loved it! From there the haystacks were taken to the thresher, which got all the corn out of it. The corn produced in Britain during the war was not good quality. All the loaves were slightly brown. This was because most of the corn was shipped here from the prairies of America and Canada on ships that Hitler tried to sink in the Atlantic war. He wanted to starve Britain. They would pick up the poor-quality corn from our farms and mix it with the better white corn from across the ocean. We did not know this when we were kids; it was just normal to us! Back to School The work on the farm only lasted for eight weeks. After that, I had to go back to school. Winter was coming on when I returned, and the school was having a bit of a problem: it did not have a caretaker because he was in the army. Billy Sherwood, the headmaster, would say, "Helsdown, go and prepare the boiler," because it was getting colder. He knew I was not really interested in being at school, so I was given odd jobs like that. I would shut everything down at night, and then, when I arrived in the morning, I would go straight down to the boiler room, move the really big, difficult grate, and put the new coal on. I joined the class again when I was ready. Nowadays, they would not trust kids to do a job like that. It is all automatic now anyway! |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|